18 Turbulence

Turbulence is perhaps the most beautiful unsolved problem of classical physics. History of turbulence in interplanetary space is, perhaps, even more interesting since its knowledge proceeds together with the human conquest of space. The behavior of a flow which rebels against the deterministic rules of classical dynamics is called turbulent. Practically turbulence appears everywhere when the velocity of the flow is high enough. At a first sight turbulence looks strongly irregular and chaotic, both in space and time: it seems to be impossible to predict any future state of the motion. However, it is interesting to recognize the fact that, when we take a picture of a turbulent flow at a given time, we see the presence of a lot of different turbulent structures of all sizes which are actively present during the motion. We recognize that the gross features of the flow are reproducible but details are not predictable. We have to use a statistical approach to turbulence, just as it is done to describe stochastic processes, even if the problem is born within the strange dynamics of a deterministic system.

Small fluctuations in plasmas lead to turbulence, and turbulent eddies can very effectively transport mass, momentum and heat from the hot core across confining magnetic field lines out to the cooler plasma edge. Predicting this phenomenon of turbulent-transport is essential for solar wind study and the understanding and development of fusion reactors.

Turbulence became an experimental science since Osborne Reynolds who, at the end of 19th century, observed and investigated experimentally the transition from laminar to turbulent flow. He noticed that the flow inside a pipe becomes turbulent every time a single parameter, a combination of the mass density \(\rho\), viscosity coefficient \(\eta\), a characteristic velocity \(U\), and length \(L\), would increase. This parameter \(\text{Re} = UL\rho/\eta\) is now called the Reynolds number. When \(\text{Re}\) increases beyond a certain threshold of the order of \(\text{Re}\simeq 4000\), the flow becomes turbulent.

Predictability in turbulence can be recast at a statistical level. In other words, when we look at two different samples of turbulence, even collected within the same medium, we can see that details look very different. What is actually common is a generic stochastic behavior. This means that the global statistical behavior does not change going from one sample to the other. Fully developed turbulent flows are extremely sensitive to small perturbations but have statistical properties that are insensitive to perturbations. Fluctuations of a certain stochastic variable \(\psi\) are defined as the difference from the average value \(\delta\psi = \psi - \left< \psi \right>\), where brackets mean some averaging process. There are, at least, three different kinds of averaging procedures that may be used to obtain statistically-averaged properties of turbulence:

- Space averaging over flows that are statistically homogeneous over scales larger than those of fluctuations.

- Ensemble averaging where average is taken over an ensemble of turbulent flows prepared under nearly identical external conditions. Each member of the ensemble is called a realization.

- Time averaging, which is useful only if the turbulence is statistically stationary over time scales much larger than the time scale of fluctuations. In practice, because of the convenience offered by locating a probe at a fixed point in space and integrating in time, experimental results are usually obtained as time averages. The ergodic theorem (Halmos, 1956) assures that time averages coincide with ensemble averages under some standard conditions.

A different property of turbulence is that all dynamically interesting scales are excited, that is, energy is spread over all scales and a kind of self-similarity is observed.

Since fully developed turbulence involves a hierarchy of scales, a large number of interacting degrees of freedom are involved. Then, there should be an asymptotic statistical state of turbulence that is independent on the details of the flow. Hopefully, this asymptotic state depends, perhaps in a critical way, only on simple statistical properties like energy spectra, as much as in statistical mechanics equilibrium where the statistical state is determined by the energy spectrum (Huang, 1987). Of course, we cannot expect that the statistical state would determine the details of individual realizations, because realizations need not to be given the same weight in different ensembles with the same low-order statistical properties.

It should be emphasized that there are no firm mathematical arguments for the existence of an asymptotic statistical state. Reproducible statistical results are obtained from observations, that is, it is suggested experimentally and from physical plausibility. Apart from physical plausibility, it is embarrassing that such an important feature of fully developed turbulence, as the existence of a statistical stability, should remain unsolved. However, such is the complex nature of turbulence.

Amitava Bhattacharjee gave a nice tutorial on the MHD turbulence in space plasmas.

18.1 Weak and Strong Turbulence

Weak turbulence

- Nonlinearity: Interactions between waves or eddies are weak in the sense that the energy in these interactions is much smaller than the total energy of the system.

- Perturbative Approach: Weak turbulence theory is often treated via a perturbative expansion where nonlinear terms are considered small corrections to the linear behavior of waves. This allows for an analytical treatment of wave-wave interactions.

- Three-wave interactions: The fundamental interactions involve three waves satisfying resonance conditions in frequency and wavenumber (e.g., two waves combining to form a third wave).

- Predictability: Since the interactions are weak, the time evolution of the system is relatively predictable, and statistics of the turbulent state can be calculated more directly.

- Energy Cascades: Energy still gets transferred across scales from large to small, creating a characteristic energy spectrum.

Strong turbulence

- Intense Nonlinearity: Interactions between waves or eddies become comparable in strength to the total energy of the system. Linear wave descriptions break down significantly.

- Complex Interaction Web: Simple three-wave interactions no longer fully describe the behavior. More complex, multi-wave interactions and turbulent structures play a dominant role.

- Less Analytical Tractability: Strong turbulence is difficult, often impossible, to fully solve analytically, because linear approximation no longer works. Numerical simulations and phenomenological modeling become essential tools.

- Chaotic Behavior: The system can show extreme sensitivity to initial conditions, making long-term predictions about the detailed evolution very challenging.

- Energy Cascades and Dissipation: The transfer of energy across scales becomes more rapid, and may no longer follow simple power-law energy spectra like in weak turbulence. Dissipation at small scales becomes significant.

In the context of water waves, an example of weak turbulence is the small ripples on a relatively calm pond, and an example of strong turbulence is the crashing waves on a stormy ocean. Intuitively, we can tell that the weak turbulence is easier to describe mathmatically than the strong turbulence.

18.2 MHD

Nunov highly recommended a review (Schekochihin 2022). Another nice reference for the solar wind turbulence is presented (Bruno and Carbone 2013), where I cite many materials in this note.

Magnetohydrodynamic turbulence concerns the chaotic regimes of magnetofluid flow at high Reynolds number. Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) deals with what is a quasi-neutral fluid with very high conductivity. The fluid approximation implies that the focus is on macro length-and-time scales which are much larger than the collision length and collision time respectively.

The guide magnetic field in turbulence is usually considered as the steady state background field. It can either be imposed by external sources, or created by large-scale eddies.

18.2.1 Comparison with Hydrodynamics

- HD turbulence: interaction of eddies.

- MHD turbulence: interaction of wave packets moving with Alfvén velocities.

18.2.2 Incompressible MHD equations

In the context of studying turbulence, the most commonly used math tool is the incompressible MHD equations. Incompressibility means \(\nabla\cdot\mathbf{u}=0\), but not necessarily constant density. Physically it means infinite sound speed \(V_s \sim \sqrt{\delta p / \delta \rho}\to \infty\), i.e. the density will not change no matter how large the pressure variation is. In many scenarios, assuming constant density is good enough and lead to further simplification of math.1

The incompressible MHD equations for constant mass density, \(\rho=1\), are \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial\mathbf{u}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{u}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u} &= -\nabla P + \mathbf{B}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{B} + \nu\nabla^2\mathbf{u} \\ \frac{\partial\mathbf{B}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{u}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{B} &= \mathbf{B}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u} + \eta\nabla^2\mathbf{B} \\ \nabla\cdot\mathbf{u} &= 0 \\ \nabla\cdot\mathbf{B} &= 0 \end{aligned} \tag{18.1}\] where \(P\) is the total (thermal + magnetic) pressure, \(\nu\) is the kinematic viscosity, and \(\eta\) is the magnetic diffusivity. In the above equation, the magnetic field is in Alfvén units (same as velocity units).

The total magnetic field can be split into a mean field \(\mathbf{B}_0\) and a fluctuating field \(\mathbf{b}\): \[ \mathbf{B} = \mathbf{B}_0 + \delta\mathbf{b} \]

We can then obtain the magnetic field equation for the perturbation term only: \[ \frac{\partial\mathbf{b}}{\partial t} = \mathbf{v}_A\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u} + \mathbf{b}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u} \]

If the Hall effect is considered, then there will be additional terms in the magnetic field equation \[ \frac{\partial\mathbf{b}}{\partial t} = \mathbf{v}_A\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u} + \mathbf{b}\cdot\nabla\mathbf{u} + d_i\nabla\times\left[ \mathbf{v}_A\times(\nabla\times\mathbf{b}) \right] + d_i\nabla\times\left[ \mathbf{b}\times(\nabla\times\mathbf{b}) \right] + \eta \nabla^2\mathbf{b} \tag{18.2}\]

The symmetric forms of \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) hint us that we may be able to combine them together; this is exactly what Walter Elsässer did back in 1950.

18.2.3 Coupling between charged fluid and magnetic field

Elsässer variables are used to extract the Alfvénic component from MHD. The perturbations in Elsässer form are written as \[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{z}^+ &= \delta\mathbf{v} + \delta\mathbf{b} \\ \mathbf{z}^- &= \delta\mathbf{v} - \delta\mathbf{b} \end{aligned} \tag{18.3}\] where \(\mathbf{b} = \mathbf{B}/\sqrt{\mu_0\rho}\) or \(\mathbf{b} = \mathbf{B}/\sqrt{4\pi\rho}\) in CGS units.

\(\mathbf{z}^\pm\) corresponds to anti-parallel/parallel propagating modes:

- Parallel wave: \(\delta\mathbf{v}=-\delta\mathbf{b}\Rightarrow \mathbf{z}^+=0, \mathbf{z}^-=2\delta\mathbf{v}\)

- Anti-parallel wave: \(\delta\mathbf{v}=\delta\mathbf{b}\Rightarrow \mathbf{z}^+=2\delta\mathbf{v}, \mathbf{z}^-=0\)

Note that each field can contain multiple fluctuating modes: \(\mathbf{z}^- = \sum_{k} \mathbf{z}_k^-\), \(\delta\mathbf{B} = \sum_{k} \delta\mathbf{B}_k\). \(\mathbf{z}^\pm\) is a field quantity.

The Alfvénicity condition \[ \delta\mathbf{v}=\pm\delta\mathbf{b}=\pm\delta\mathbf{B}/\sqrt{\mu_0\rho_0} \tag{18.4}\] often appears in the context of discussing Alfvén waves.

The incompressible MHD wave equation in fluctuating Elsässer form is: \[ \frac{\partial\mathbf{z}^\pm}{\partial t} \mp \mathbf{v}_A\cdot\nabla_\parallel\mathbf{z}^\pm + \mathbf{z}^\mp\cdot\nabla\mathbf{z}^\pm = -\nabla p + \nu_+ \nabla^2 \mathbf{z}^{\pm} + \nu_- \nabla^2 \mathbf{z}^{\mp} \tag{18.5}\] where \(\nu _{\pm}=\frac{1}{2}(\nu \pm \eta)\). The incompressibility and divergence-free B condition are written as \[ \nabla\cdot\mathbf{z}^\pm = 0 \tag{18.6}\]

The zero divergence means that there are no forcing or dissipation terms. Since we have already assumed uniform density in Equation 18.1, \(v_A = B_0 / \rho = B_0\), we can write Equation 18.5 in an alternative form \[ \frac{\partial\mathbf{z}^\pm}{\partial t} \mp \mathbf{B}_0\cdot\nabla_\parallel\mathbf{z}^\pm + \mathbf{z}^\mp\cdot\nabla\mathbf{z}^\pm = -\nabla p + \nu_+ \nabla^2 \mathbf{z}^{\pm} + \nu_- \nabla^2 \mathbf{z}^{\mp} \tag{18.7}\]

Equation 18.5 unveils the interesting phenonmena in Alfvénic turbulence study. The second term on the left-hand side is a linear term that represents propagation of waves parallel to the mean field. The third term represent the non-linear interaction of counter-propagating waves, during which energy is transferred to smaller scales. This is exactly turbulence. In MHD, turbulence is manifested by the collision of Alfvén waves.

Using the linear perturbation theory, \(\mp \mathbf{v}_A\cdot\nabla_\parallel\mathbf{z}^\pm\) scales as \((k_\parallel v_A)z^\pm\), and \(\mathbf{z}^\mp\cdot\nabla\mathbf{z}^\pm\) scales as \((k_\perp z^\mp)z^\pm\). When \(k_\parallel v_A \gg k_\perp z^\mp\), the turbulence is weak; when \(k_\parallel v_A \simeq k_\perp z^\mp\), the turbulence is strong. Assuming an energy supply at small k, then first in the weak MHD turbulence the energy \(E(k_\perp)\propto k_\perp^{-2}\), and later in the strong MHD turbulence \(E(k_\perp)\propto k_\perp^{-3/2}\). At larger k, eventually we will encounter the dissipation scale, where the slope changes sharply because of the balance/imbalance of the energy cascade of the interacting waves.

Several mechanisms may happen in the dissipation scale [Huang, Howes, McCubbin, 2024]: * Transit-Time Damping (TTD): analogy to Landau damping for magnetic field, also known as Barnes damping. Particles can be energized by mirror fields by first being accelerating by an induced electric field in the perpendicular direction (as opposed to Landau damping where the energy transfer occurs in the parallel direction), and then got transferred to the parallel direction. (Also appear in Section 14.2, since it is closely related to mirror modes.) When an electromagnetic wave propagates through a plasma with varying magnetic field strength, its electric and magnetic fields oscillate. If the frequency of these oscillations matches the natural frequency at which particles are reflected by the magnetic mirror force (2nd adiabatic motion?), a resonance occurs. During this resonance, particles effectively “surf” on the wave, gaining energy from it. This energy gain comes at the expense of the wave, causing it to damp. The energy gained by the particles is primarily in the direction perpendicular to the magnetic field. TTD is a collisionless damping mechanism, which has a unique signature in velocity space. It creates a bipolar pattern of energy transfer, where some particles gain energy and others lose energy, centered around a resonant velocity. The strength of TTD is directly related to the gradient in the magnetic field strength: a stronger gradient leads to more efficient damping.

When the nonlinear term can be neglected, we have normal mode waves. For a system with only \(\mathbf{z}^+\), \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}^+}{\partial t} - \mathbf{V}_A \cdot\nabla \mathbf{z}^+ = 0 \\ \rightarrow \mathbf{z}^+ \sim f(\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{V}_A t) \end{aligned} \tag{18.8}\]

For a system with only \(\mathbf{z}^-\), \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}^+}{\partial t} + \mathbf{V}_A \cdot\nabla \mathbf{z}^+ = 0 \\ \rightarrow \mathbf{z}^+ \sim f(\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{V}_A t) \end{aligned} \tag{18.9}\] where \(\mathbf{x}\) is the coordinate parallel to \(\mathbf{B}\). Both Equation 18.8 and Equation 18.9 give the Alfvén normal modes \[ \omega = |k_\parallel| V_A \tag{18.10}\]

An interesting question is: Does an MHD Alfvén wave have more energy in its magnetic fluctuations or more energy in its velocity fluctuations?

Answer: Same energy in fluctuations of both types, since an MHD Alfvén wave either has only \(z^+\) or only \(z^-\).

Alfvénic quasimode: Nonlinearly driven, non-normal mode that need not satisfy an Alfvén wave dispersion relation but still retains some Alfvénic properties such as incompressibility and a high degree of correlation between \(\delta\mathbf{b}\) and $$.

Consider a mode \(z_3^-\) that results from the nonlinear interaction of modes \(z_1^-\) and \(z_2^+\), \(z_3^- = z_1^- z_2^+\). Because the nonlinear term is important, \[ \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}_3^-}{\partial t} + \mathbf{V}_A\cdot\nabla \mathbf{z}_3^- \neq 0 \rightarrow \omega_3 - k_{3\parallel}V_A \neq 0 \]

Question: Consider a fluctuation in incompressible MHD that is part of a larger system of many interacting modes. If the fluctuation exists only on \(z^+\) with no \(z^-\) component, what does it indicate?

Answer: No \(z^-\) component means \(z^- = \delta\mathbf{v} - \frac{\delta\mathbf{B}}{\sqrt{4\pi\rho}} = 0\), which leads to in-phase magnetic field and velocity fluctuations. However, it does not mean that it must be an Alfvén wave traveling in one direction? (Ask Seth!)

18.2.4 Importance of Alfvén Waves

- Alfvén Waves can scatter fast ions in tokamak plasmas.

- Alfvén Waves may contribute to coronal heating.

- Alfvén Waves are the building blocks for more complicated structures and dynamics, and most notably, turbulence.

18.2.5 Wave Interaction Phenomenology

From Equation 18.5, we can study the nonlinear interaction of wave modes. Consider a mode \(z_3^-\) that results from the nonlinear interaction of modes \(z_1^-\) and \(z_2^+\): \(z_3^- = z_1^- z_2^+\). The simplest three-wave interaction of shear-Alfvén waves is given as \[ \begin{aligned} \omega(k) &= \omega(k_1) + \omega(k_2) \\ \mathbf{k} &= \mathbf{k}_1 + \mathbf{k}_2 \end{aligned} \tag{18.11}\] where \[ \omega(k) = |k_z|v_A \]

In a simple version, we can write down as \[ \begin{aligned} \omega_3 = \omega_1 \pm \omega_2 \\ k_{3\parallel} = k_{1\parallel} \pm k_{2\parallel} \end{aligned} \]

The total wave number k is composed of two parts: \(k_z\) is the wave number along the guide field direction, and \(k_\perp\) is the wave number perpendicular to the guide field. Since only counter-propagating waves interact, \(k_{1z}\) and \(k_{2z}\) should have opposite signs. In order to satisfy the interaction condition, we can have either \(k_{1z} = 0\) or \(k_{2z} = 0\). That means wave interactions change \(k_\perp\) but not \(k_z\). This was verified in lab experiments with two counter-propagating modes, where we can isolate single interaction for detailed study (e.g. Howes+ 2012). An interesting point is that while from incompressible ideal MHD prediction, two modes moving along the same direction cannot have nonlinear interactions, one lab experiment showed that this is not true. This is attributed to the Hall effect, which adds additional complexity to the equations.

18.2.6 Nondimensional parameters

The important nondimensional parameters for MHD are

Reynolds number: \(\text{Re}=UL/\nu\)

Magnetic Reynolds number: \(\text{Re}_{M}=UL/\eta\)

Magnetic Prandtl number: \(P_{M}=\nu/\eta\)

The magnetic Prandtl number is an important property of the fluid. Liquid metals have small magnetic Prandtl numbers, for example, liquid sodium’s $P_{M} is around \(10^{-5}\). But plasmas have large \(P_{M}\).

The Reynolds number is the ratio of the nonlinear term \(\mathbf{u} \cdot \nabla \mathbf{u}\) of the Navier–Stokes equation to the viscous term. While the magnetic Reynolds number is the ratio of the nonlinear term and the diffusive term of the induction equation.

In many practical situations, the Reynolds number Re of the flow is quite large. For such flows typically the velocity and the magnetic fields are random. Such flows are called to exhibit MHD turbulence. Note that \(\text{Re}_{M}\) need not be large for MHD turbulence. \(\text{Re}_{M}\) plays an important role in dynamo (magnetic field generation) problem.

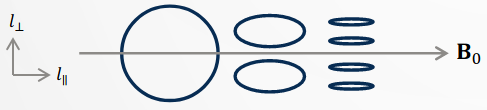

The mean magnetic field plays an important role in MHD turbulence, for example it can make the turbulence anisotropic; suppress the turbulence by decreasing energy cascade etc. The earlier MHD turbulence models assumed isotropy of turbulence, while the later models have studied anisotropic aspects.

18.2.7 Critical balance

Polarized Alfvén modes interact. Due to the dot product in the nonlinear term in Equation 18.5, only the perpendicularly polarized components of the modes interact. The strength of the interaction can be quantified as \[ \chi \sim \frac{k_\perp z^\mp}{k_\parallel V_A} \]

If we match the Alfvén (linear) timescale, \(\tau_A \sim l_\parallel/v_A\) (related to how fast Alfvén waves propagate along magnetic field lines), with the nonlinear timescale, \(\tau_{nl}\sim l_\perp/\delta z\) (related to how fast turbulent eddies interact and distort each other), \[ \tau_A = \tau_{nl} \] we have a way to predict the scaling of energy distribution across different scales, and the relationship between perpendicular and parallel structures in turbulence. This is known as the critical balance (Goldreich and Sridhar 1995), where \(\chi\sim 1\), as is assumed in solar wind turbulence.

Assume a constant energy cascade rate \(\epsilon\sim \delta z^2/\tau_{nl}\), and an energy injection rate at scale L \(\epsilon_L\sim v_A^2/\tau_{nl}=v_A^3/L\). When we match the two rates and … (I have some memory from Nunov’s lecture at Nordita), we have \[ k_\parallel\propto k_\perp^{2/3} \tag{18.12}\] This means that anisotropy grows with decreasing scale. It indicates the transition from “weak” to “strong” turbulence, or more accurately a transition from “quasi-linear” to “mode-coupling” processes.2 The power spectra are given as \[ \begin{aligned} E(k_\perp) &\propto k_\perp^{-5/3} \\ E(k_\parallel) &\propto k_\parallel^{-2} \end{aligned} \tag{18.13}\]

This is among the most influential discoveries related to MHD turbulence, which makes it distinct from gas dynamic Kolmogorov turbulence by taking the magnetic field into account. By separating \(k_\parallel\) and \(k_\perp\) dynamics, the critical balance theory predicts perpendicular energy spectra Equation 18.13, which is consistent with the solar wind turbulence in the inertial range [Chen 2016]. The theory invoking this concept is now known as the anisotropic MHD turbulence.

However, why this is the case in nature is still under debate.

18.2.8 Residual energy

Residual energy is the difference in energy between magnetic and velocity fluctuations. The normalized residual energy is \[ \sigma_r = \frac{|\delta\mathbf{v}|^2 - |\delta\mathbf{b}|^2}{|\delta\mathbf{v}|^2 + |\delta\mathbf{b}|^2} \tag{18.14}\]

\(\sigma_r\) is zero for an Alfvén wave but is generally negative (\(|\delta\mathbf{b}|^2 > |\delta\mathbf{v}|^2\)) at MHD scales for solar wind observations, meaning that they are mostly likely turbulence but not waves.

Weak MHD turbulence spontaneously generates a condensate of the residual energy \(E_r = E_b - E_k\) at small \(k_\parallel\). Condensate broadens with \(k_\perp\).

For Strong MHD turbulence, the residual energy is nonzero at all k.

18.2.9 Normalized cross helicity

Cross helicity is the difference in energy between \(\mathbf{z}^+\) and \(\mathbf{z}^-\) fluctuations (Section 19.5). The normalized cross helicity is \[ \sigma_c = \frac{|\mathbf{z}^+|^2 - |\mathbf{z}^-|^2}{|\mathbf{z}^+|^2 - |\mathbf{z}^-|^2} = \frac{2\delta\mathbf{v}\cdot\delta\mathbf{b}}{|\delta\mathbf{v}|^2 + |\delta\mathbf{b}|^2} \tag{18.15}\]

- \(|\sigma_c|=1\): unidirectional Alfvén waves (no turbulence)

- \(|\sigma_c|\lesssim 1\): imbalanced turbulence

- \(|\sigma_c|=0\): balanced turbulence (or non-Alfvénic fluctuations)

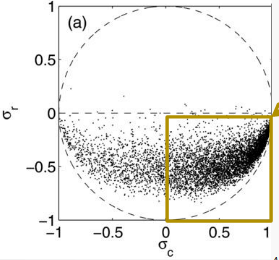

The solar wind is typically imbalanced towards the anti-sunward direction. From Equation 18.14 and Equation 18.15 we can easily see that \[ \sqrt{\sigma_r^2 + \sigma_c^2} \le 1 \]

The observed distribution is shown in Figure 18.1. Note, however, \(\sigma_r\) depends on how you evaluate \(\delta{b}\). In the MHD case \(\mathbf{b} = \mathbf{B}/\sqrt{\mu_0\rho}\) is used, but in the kinetic case there will be an extra coefficient. The results look pretty different!

Observation from 1 AU (WIND) show that the non-Alfvénic wind typically has small alpha-proton relative drift and nearly equal temperatures of both ionic components. In terms of occurrence, there is no significant difference for a typical solar wind speed of 300 km/s, but for high speed solar wind there is a higher probability for large \(|\sigma_c|\) of being Alfvénic.

- Non-Alfvénic solar winds

- slower and lower in abundance, \(n_\alpha/n_p < 4%\)

- \(v_p - v_\alpha \sim 0\)

- \(T_p \sim T_\alpha\)

- could be formed by the interchange-recnnection near the Sun

- Alfvénic solar winds

- \(n_{\mathrm{He}}/n_{\mathrm{p}}\sim 4%\) and does not depend on the proton velocity

- alpha particles are about 4 times hotter than protons.

- originates from the coronal holes

18.3 Solar Wind Turbulence

18.3.1 Taylor’s hypothesis

Solar wind is a supersonic flow (\(v_A/v_{\text{SW}}\ll 1\)), with advection timescale much shorter than any dynamical timescales in the plasma. This means that for spacecraft observations, the time series represents an instantaneous spatial cut through the solar wind plasma. We can thus relate spacecraft frequency, \(f_{\text{sc}}\), to wavenumber in the plasma frame, \(k\), in a simple way via \[ k = \frac{2\pi f_\text{sc}}{v_\text{SW}} \]

This is often not appropriate in the magnetosheath, and modified Taylor’s hypothesis is required close to the Sun.

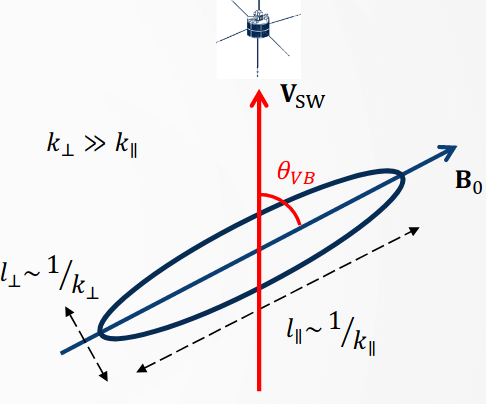

The wavenumber \(k\) determined from Taylor’s hypothesis is really the flow-aligned component of \(\mathbf{k}\). For a given angle \(\theta_{vb}\), one cannot distinguish \(k_\perp\) and \(k_\parallel\); these can be possibly measured for small (\(\sim 0^\circ\) for \(k_\parallel\)) and large (\(\sim 90^\circ\) for \(k_\perp\)) at different times. In the solar wind, \(P(k_\perp) \gg P(k_\parallel)\), where \(P\) is the power of perturbation. For a Parker spiral-like magnetic field at 1 AU, the angle between \(\mathbf{B}_0\) and \(\mathbf{v}_\text{sw}\) is rarely small (\(\sim 45^\circ\)), the power spectra are typically dominated by the contribution from the \(k_\perp\) fluctuations (Figure 18.2).

18.3.2 Solar Wind Power Spectrum

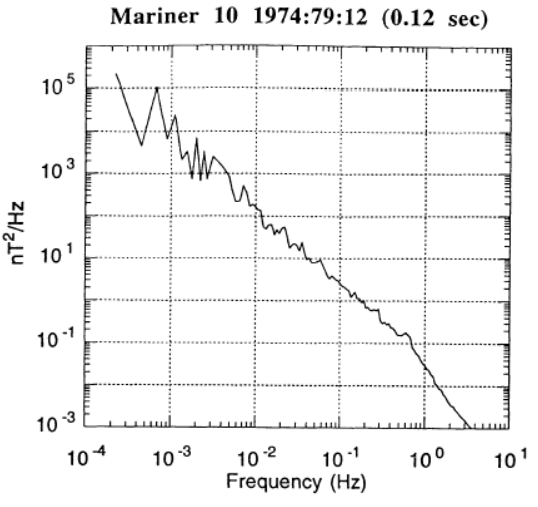

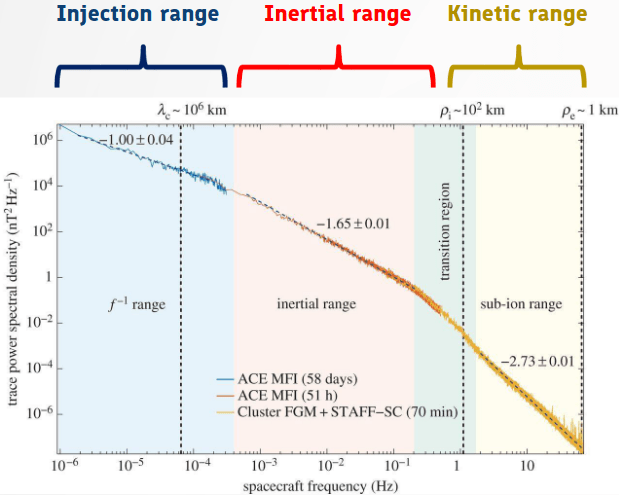

When we plot the solar wind power spectrum (\(\delta|\mathbf{B}|\)) as a function of time, it is usually representative of \(k_\perp\)3. There are three distinct power-law ranges in the spectrum from spacecraft solar wind observations (Figure 18.4):

- Injection range:

- Large amplitude, low frequency Alfvén waves originating from the Sun.

- The \(f^{-1}\) spectrum is known as the “pink noise”.

- Non-interacting

- Inject energy to the MHD cascade at higher frequencies

- Inertial range:

- Mostly incompressible Alfvénic turbulence.

- \(\sim f^{-5/3}\) spectrum (Kolmogorov type)

- a cascade of energy to smaller scales

- Kinetic range:

- Scales at which particles are heated

- Typically \(f^{-2.8}\) spectrum

- Possibly KAW (Section 10.8.4) or whistler mode (Section 10.6) turbulence

When we move to smaller scales, anisotropy increases. This is demonstrated in Figure 18.5 as a result of \(k_\perp \gg k_\parallel\), which is also why gyrokinetics is the theory for turbulence. Isotropic MHD is inadequate in turbulence study because of this major drawback.

Fluctuation modes in the inertial range consists of 90% incompressible (Alfvén) modes and 10% compressible slow/mirror modes. Alfvénic turbulence is thought to be passive to the compressive modes: compressive modes scatter off Alfvén modes without affecting them significantly (i.e. being decoupled from each other). The compressive modes are expected to damp \(\sim k_\parallel v_A\). Since \(k_\perp \gg k_\parallel\), the damp is not significant for compressive modes, so they tend to be more anisotropic than the Alfvénic turbulence.

18.4 Turbulence and Reconnection

Turbulence and magnetic reconnection can be mutually driven, but the underlying nature of energy dissipation, intrinsic turbulence waves, and magnetic field topologies in turbulent magnetic reconnection is still poorly understood.

To study turbulence and reconnection together, one need to confirm several things beforehand:

The existence of reconnection, from identifying magnetic null point, plasma inflow and outflow, and the diffusion regions.

The existence of turbulence, by looking at the magnetic field power spectrum and confirm the cascades. From satellite data, this is done by taking a time interval, performing FFT, and check the characteristic frequency scales such as the ion cyclotron frequency \(f_{ci}\), the lower hybrid frequency \(f_{ln}\), etc.

If there are spectral breaks in the power spectrum diagram (PSD), especially near the characteristic frequencies, they may indicate local cyclotron resonance, which is related to wave-particle interactions. Some researchers have found from MMS tail current sheet observations that in the reconnection outflow regions, energy is deposited in the form of kinetic Alfvén waves in low-frequency \(f_{ci}\) ion cyclotron scale and fast/slow waves in high-frequency low-hybrid scale.

constant density leads to incompressibility, but not vice versa.↩︎

Two Alfven wave packets moving towards each other will first be in the quasi-linear stage and then in the mode-coupling stage when they meet each other and interact nonlinearly.↩︎

Of source there is an assumption here that the spatial scale and the time scale are proportional, since we cannot measure the spectrum as a function of space directly.↩︎