23 Ionosphere

Ionosphere is like a transition region from neutral gas to plasma. Therefore, collisions as well as kinetic effects gradually become important as go down from space. Section 9.8 presents some basic physics related to the collisional effect in the ionosphere.

23.1 Current Systems

Electric fields associated with the viscous interaction and reconnection-driven plasma flow are transmitted along field lines to the ionosphere where they drive currents through the ionosphere. The high latitude FAC are known as region-1 currents, while the lower latitude currents are called region-2 currents. The ionospheric current connecting these two FAC systems flows parallel to the projected electric field and is called the Pedersen current. Since the Pedersen current flows through a resistive ionosphere in the direction of the electric field it causes Ohmic heating \(\mathbf{j}\cdot\mathbf{E}>0\). The two shells of FAC form a solenoid so that the magnetic perturbations they create are confined to the region between them and cannot be detected on the ground. Because of the interaction of the motion of ionized gases with the neutral atmosphere, the ions and electrons undergo different drift motion. Ions, due to higher collision rates with the neutral atmosphere, have a component of motion perpendicular to the \(\mathbf{E}\times\mathbf{B}\) drift direction, while the electrons generally follow \(\mathbf{E}\times\mathbf{B}\). The non-dissipative (\(\mathbf{j}\cdot\mathbf{E}=0\)) Hall current flows at right angles to both the electric and magnetic fields. The magnetic effects of the Hall current driven by the region-1 and 2 currents can be observed on the ground and are known as the DP-2 current system.1

In the context of ionospheric energy dissipation, the different current systems can be classified into two types based on how energy is processed.

- If the ionospheric motion and dissipation is coupled directly to the solar wind, the system is said to be “directly-driven”. The directly-driven process manifests itself as the DP-2 (two cell pattern) ionospheric current system.

- If magnetic energy is first stored in the tail lobes and then released some time later, driving additional convection and field-aligned and ionospheric currents, it is called “unloading”, and is associated with the DP-1 (substorm current wedge) current system.

Both processes cause precipitation of charged particles that also deposit energy in the atmosphere.

The characteristic feature of the driven DP-2 current system is the existence of the eastward and westward electrojets flowing toward midnight along the auroral oval. Rough measures of the strength of these currents are the auroral upper (AU) and auroral lower (AL) indices. These are respectively the largest positive northward magnetic perturbation (H) measured on the ground under the eastward electrojet by any magnetic observatory in the afternoon to dusk sector, and the largest negative southward perturbation measured in the late evening to morning sector. Both AU and AL begin to grow in intensity soon after the IMF turns southward and dayside reconnection begins. The characteristic feature of the unloading DP-1 current system is the sudden development of an additional westward current that flows across the bright region of the expanding auroral bulge. This is the ionospheric segment of the substorm current wedge. The onset of this current is recorded in the AL index as a sudden decrease, corresponding to an increase in intensity of the westward current.

23.2 M-I Coupling

Ionospheric properties, principally conductivity, provide boundary conditions for magnetospheric convection, and the ionosphere is often treated as a passive part of the system. Especially during substorms, however, the boundary conditions change in a time-dependent and spatially localized fashion, allowing ionospheric feedback that can alter the magnetospheric dynamics. The coupling from the ionospheric perspective differs primarily in that the ionospheric conductance is anisotropic due to the influence of the neutral atmosphere, involving Hall as well as Pedersen conductivity. These conductivities are altered both by the connecting currents and the precipitating electrons associated with upward field-aligned currents, which increase Pedersen conductivity and field line tying. An important role is also played by field-aligned electric fields, set up locally, primarily in upward field-aligned current regions, which are the cause of auroral intensifications and, specifically auroral arcs.

For magnetosphere simulations, the simplest inner boundary is treated as a conducting sphere (\(\mathbf{B}_\text{normal}=0\), \(\mathbf{E}=\mathbf{v}=0\)). However, this is often not realistic enough to reveal the nature. In magnetosphere simulations, the location of tail main reconnection site will be closer to the Earth by simply applying a conducting boundary. The next level extension is to employ a magnetospheric-ionospheric electrostatic coupling model. This means that we seek nonzero \(\mathbf{E}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) at the inner boundary. The inner boundary, where the MHD quantities are connected to the ionosphere, is taken to be a shell of radius \(r_\text{in}\) (e.g. \(r_\text{in}\sim 3\,\text{R}_\text{E}\)). The ionosphere locates at \(r_\text{ion}\sim 1000\,\text{km}\sim 0.15\,\text{R}_\text{E}\). Ideally \(r_\text{in}\) shall be as close to \(r_\text{ion}\) as possible, but typically it is restricted by computational limitations, such as extraneously high Alfvén speeds and very large \(\mathbf{B}\) field gradients closer to the Earth. Inside this shell we do not solve the governing equations (MHD/PIC/Vlasov), but assume a static dipole field. The important physical processes within the shell are the flow of field-aligned currents (FACs) and the closure of these currents in the ionosphere. At each time step,

The magnetospheric FACs are mapped along the field lines from the inner boundary to the ionosphere assuming \(j_\parallel/B=\text{const.}\), which are the input to the ionospheric potential equation (Raeder, Walker, and Ashour-Abdalla 1995) \[ \nabla\cdot(\pmb{\Sigma}\cdot\nabla\Phi) = -j_\parallel\sin I \tag{23.1}\] where \(\pmb{\Sigma}\) is the conductance tensor, \(\Phi\) is the electric potential, \(j_\parallel\) is the mapped FAC density with the downward considered positive and corrected for flux tube convergence, and \(I\) is the inclination of the dipole field at the ionosphere, \(\sin I=\cos(\frac{\pi}{2}-I)=\hat{b}\cdot\hat{r}\). The derivation from the charge conservation can be found in Section 9.8.7. There is another form derived by [Wolf 1983]: \[ \nabla_\perp\cdot \begin{pmatrix} \sigma_P/\cos^2\delta & -\sigma_H\cos\delta \\ \sigma_H/\cos\delta & \sigma_P \end{pmatrix} \cdot\nabla_\perp\Phi = j_\parallel\cos\delta \tag{23.2}\] where \(\delta\) is the magnetic field dip angle: \[ \cos\delta = -2\frac{\cos\theta}{\sqrt{1+3\cos^2\theta}} \] for the northern hemisphere, where \(\theta\) is the polar angle (magnetic colatitude). I DON’T KNOW THE RELATION BETWEEN THESE TWO!

Equation 23.1 is solved on the surface of a sphere \(r=r_\text{ion}\). Commonly there are two types of boundary conditions: (1) \(\Phi=0\) at the equator (Raeder, Walker, and Ashour-Abdalla 1995), or (2) constant potential at or near the low‐latitude boundary (e.g. LFM, BATSRUS). From here, one can either choose a static analytic model of Hall and Pederson conductance that accounts for multiple physics, or simply adopt a uniform Pederson conductance, or the height-integrated conductivity, \(\Sigma_p = 5\,\text{Siemens}\), while the Hall conductance \(\Sigma_H\) is assumed to be zero. The latter one is simplified to solve \[ \nabla^2\Phi = -j_\parallel\sin I/\Sigma_p \]

A more realistic conductance requires considering EUV and diffuse auroral contributions (???) as well. The solar EUV contribution to \(\pmb{\Sigma}\) is considered constant in time, but naturally it varies with the solar zenith angle. For example, the empirical formulas by [Moen and Brekke 1993] can be used. The solar EUV radiation is approximated by the 10.7 cm radio flux (commonly known as F10.7), a widely used proxy solar UV activity, whose standard values is taken to be \(100\times 10^{-22}\,\text{W}/\text{m}^2\).

The total conductance can be then expressed as \[ \Sigma_{P,H} = \sqrt{(\Sigma_{P,H}^{e-})^2 + (\Sigma_{P,H}^{\text{UV}})^2} \]

This is because \(\sigma_{P,H}\propto n_e\), which in a stationary state is proportional to the square root of the production rate, and it is the production rates that can be summed linearly. (???)

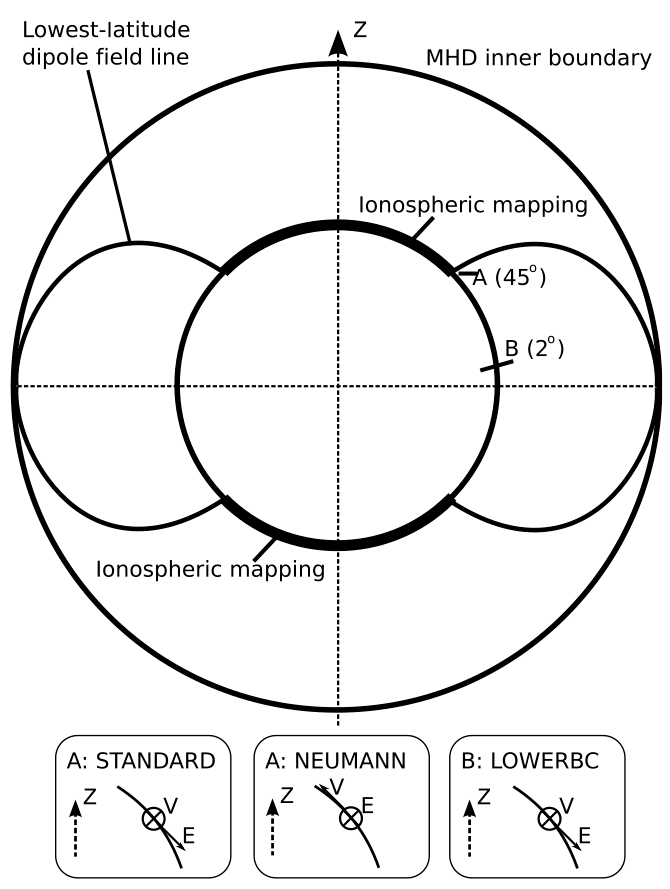

Does this look well? Not yet. We know that while the high‐latitude ionospheric convection is driven by the solar wind and magnetosphere interaction, at lower latitudes atmospheric neutral winds start to dominate. The next level approximation needs to take this into account. Because there is a gap between \(r_\text{ion}\) and \(r_\text{in}\), the ionospheric footprint of their grid has a low‐latitude boundary somewhere in the midlatitudes, e.g., 45° when \(r_\text{in}\sim 2\,\text{R}_\text{E}\) (Figure 23.1). Global magnetospheric models, unless they are fully coupled to models of the inner magnetosphere and the ionosphere, lack details of the ionospheric convection at latitudes equatorward of their low‐latitude ionospheric boundary. To some extent, such details can be translated to the global model via the low‐latitude boundary condition used to solve Equation 23.2. The easy way is to set the ionospheric potential to zero everywhere on the boundary. This corresponds to no flow across the boundary in the ionosphere or the inner boundary of the magnetosphere simulation in the equatorial plane. The choice of this boundary condition is usually justified by the argument that it helps to shield the inner magnetosphere from the cross‐tail electric field.

(Merkin and Lyon 2010) tested three different boundary conditions for the potential equation:

- STANDARD: Dirichlet, the potential at the low‐latitude boundary is set to zero.

- NEUMANN: the electric field component normal to the low‐latitude boundary was set to zero. This condition requires all ionospheric plasma to move normal to the boundary.

- LOWERBC: Dirichlet, but the location of the low‐latitude boundary was moved to 2° above the equator, thus allowing the plasma to move across the magnetosphere inner boundary. (???) Equation 23.3 is singular at \(\theta=\pi/2\), which is why the calculation has to stop just short of the equator. (???)

Sparse linear algebra, GMRES together with an imcomplete LU preconditioner (default for many modern solvers) are usually applied to solve the potential equation. This is generally an easy equation to solve mathematically.

Once the potential equation is solved the ionospheric potential is mapped back to the \(r_\text{in}\) shell and used as a boundary condition for the magnetospheric flow by taking \(\mathbf{v}=(-\nabla\Phi)\times\mathbf{B}/B^2\).

23.2.1 Caveats

- The mapping assumes conservation, which is not perfect. In practice \(r_\text{in}\sim 4\,\text{R}_\text{E}\) is a minimum requirement for reasonable FACs.

- Most numerical codes couples a Cartesian grid to a spherical ionosphere grid, while some couples a spherical grid to a spherical grid. For magnetosphere simulations we need a relatively simple but super fast electric potential solver, therefore structured mesh is often adopted. If a spherical grid is used, care must be taken near the pole since it is a singular from the grid but not physics. Equation 23.2 under spherical coordinates is written as

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{\sin\theta}&\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\Big[ \sin\theta\frac{\Sigma_P}{\cos^2\delta}\frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial\theta} - \frac{\Sigma_H}{\cos\delta}\frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial\phi} \Big] \\ + &\frac{\partial}{\partial\phi}\Big[ \frac{\Sigma_P}{\sin^2\theta}\frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial\phi}+\frac{\Sigma_H}{\sin\theta\cos\theta}\frac{\partial\Phi}{\partial\theta} \Big] = j_\parallel R^2\cos\delta \end{aligned} \tag{23.3}\]

Be careful about distinguishing \(E_\parallel\) and \(j_\parallel\). \(E_\parallel = 0\) from advection and Hall terms, but \(j_\parallel=\nabla\times\mathbf{B}\cdot\hat{b}/\mu_0\) can be nonzero at the MHD inner boundary.

How important it is to use a more realistic conductance model? (Merkin and Lyon 2010) shows that different BCs may give > 10% CPCP values, but I have no clue about the effect of a more complicated conductance.

23.3 Ionosphere Modeling

- What equation set is the model solving? How is the model solving them? What is being neglected?

- What species are included? How is the chemistry solved?

- Parameterizations in things such as heating, cooling, viscosity, conduction, chemistry, diffusion, collision, absorption, ionization cross sections, reaction rates…

- How are upper and lower boundaries treated? How is the pole or the open/closed field-line boundary treated?

- How are electrodynamics considered? How is the aurora specified? How is the magnetospheric electric field imposed? Is ion precipitation considered?

For an ionosphere, a magnetic field-aligned grid is often used. This is complicated by the non-orthogonal nature of the magnetic field coordinate system. Assumptions are made.

How to solve each direction (coupled or independently)? For the ionosphere, along the field-line is treated differently than across the field-lines.

As the equations of motion are solved for, the source terms must be added. How to treat these with respect to solving in the different directions?

Build a simple 1D ionosphere model is easy (CAN I MAKE ONE MYSELF?).

Steady-state - assume \(\partial \mathbf{X}/\partial t = 0\). Strangly, this is applied in situations in which the value can change on a time scale much faster than the time-step. For example, the ion velocity is often assumed to be steady-state. Ion chemistry is sometimes assumed to be steady-state.

23.3.1 Chemistry

\[ \frac{\partial N}{\partial t} = S - L \] where \(N\) is the number density of the species, \(S\) represents the sources and \(L\) represents the losses. Losses can almost always be expressed as: \[ L = RMN \] where \(R\) is the reaction rate, \(M\) is the density of the species it is reacting with.

For a steady-state, \[ \begin{aligned} S - L &= 0 \\ N &= \frac{S}{RM} \end{aligned} \]

This is quite stable, but can be very wrong in regions of slowly changing ion densities, such as in the F-region. This is perfect for the E-region, though. It is quite easy to implement in a simple environment, but can be much more complicated as non-linear terms are include (recombination, in which \(M\) can depend on \(N\)).

An explicit time step chemistry is trivial to implement in almost all situations, but it is also the least stable, since the loss terms can become larger than the source terms and the density can quickly be driven to negative values. Subcycling can help with this, but not always.

An implicit time step chemistry is relatively stable and easier to implement than steady-state. For example in GITM, there is a blend between sub-cycling and a simplified implicit scheme that switches depending on the size of the loss term compared to the density.

Now we need to also look at the source terms. The ionization rates can be obtained from \(Q_\text{EUV}\) and substituting \(\sigma_s^i \lambda\) instead of \(\sigma_s^a\lambda\) (not in \(\tau\)). [Schunk and Nagy] Chapter 8 list a bunch of chemical equations.

After that, we write down all the sources and losses, decide a time-stepping scheme, and run the model. However, if we don’t have any ion advection, the F-region will just build and build!

23.3.2 Ion Advection

In the simplest form, we assume an advection speed and let the densities advect upward and downward.

23.4 Ionosphere Waveguide

The ionosphere waveguide refers to the phenomenon in which certain radio waves can propagate in the space between the ground and the boundary of the ionosphere. Because the ionosphere contains charged particles, it can behave as a conductor. The planet operates as a ground plane, and the resulting cavity behaves as a large waveguide. This is closely related to the concept of skin depth in EM and the cutoff in wave propagation.

At Earth, extremely low frequency (ELF) (< 3 kHz) and very low frequency (VLF) (3–30 kHz) signals can propagate efficiently in this waveguide. For instance, lightning strikes launch a signal called radio atmospherics, which can travel many thousands of kilometers, because they are confined between the Earth and the ionosphere. The round-the-world nature of the waveguide produces resonances, like a cavity, which are at \(\sim 7\) Hz.

A brief introduction can be found on wiki.

23.5 Incoherent Scatter Radar

Longitudinal modes:

- Langmuir wave

- Ion acoustic wave

Cascading Langmuir turbulence

dispersive, kinetic Alfven waves –> optical manifestation of dispersive bursts

Region 1 & 2 currents are currents in the magnetosphere, not ionosphere.↩︎