Wavelet Transform

There are already many nice introduction of wavelet transform, like here and the following video. This is my simple note on WT while reading those tutorials.

Before we talk about cross-wavelet transform (CWT), we need to first understand wavelet transform (WT). Conceptually wavelet transform is similar to Fourier transform, but with the main difference that *wavelets are localized in both time and frequency * whereas *the standard Fourier transform is only localized in frequency *. This means that for a given time series, Fourier analysis gives you precisely the frequency magnitude and phase across the whole time interval, but you cannot tell when in time the signal is sounded. Wavelet analysis takes the temporal extent into consideration by sacrificing the accuracy of the frequency spectrum.

The end result looks similar as if you perform a local Fourier tranform in a small time span around each time stamp (which is how the traditional spectrogram plots are done). The latter, which is also well-known, is called windowed Fourier tranform (WFT), where the FT is performed on short consecutive (overlapping or not) segments. The main limitation of this method is the lack of precision to either the time or the frequency domain. The size of the segment will determine either a high level of precision in the time domain or in the frequency domain. For example, a small window would not allow for the detection of any event larger than the window while maintaining a good localization in time. On the other end, a large window will take into account the long-term event (frequency domain) but with a high level of imprecision in the temporal domain.

Some more detailed explanation can be found in this Q&A.

Historically, the WT method was introduced in seismic research by Morlet (1983). Since then, wavelets are commonly used in geosciences as they are particularly well-suited in characterizing the “local” properties of time-series.

The joint characterization of the frequency content of the time-series in time while keeping a high level of precision in both time and frequency domains constitutes one of the WT advantages.

Time-Frequency Plane

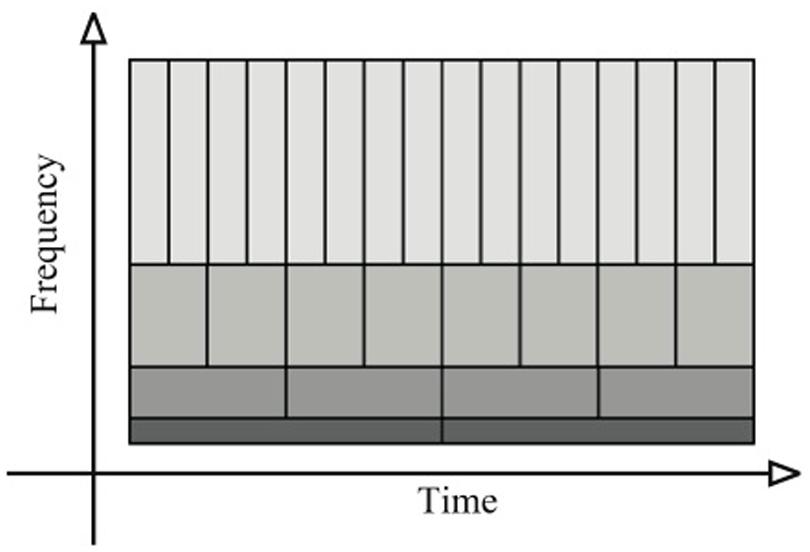

For the study of the WT, Flandrin (1988) called the time-frequency plane a scaleogram. In a scaleogram like Figure 1, we are able to perform a multi-scale analysis. One important line often shows up in a scaleogram is the cone of influence: within the region, the WT coefficient estimates are unreliable

Dilatation/Contraction/Translation of the Analyzing Function

A Wavelet is a wave-like oscillation that is localized in time.

The WT is calculated by convolving the time-series s(t) with an analyzing wavelet function ψ(a,b) (derived from a mother function ψ) by dilatation of a and translation of b.1

a: scale factor that defines how “stretched” or “squished” a wavelet is. It determines the characteristic frequency so that varyingagives rise to a spectrum.b: translation in time, i.e. the “sliding window” of the wavelet overs(t). It determines where the wavelet is positioned in time. Location is important because unlike waves, wavelets are only non-zero in a short interval. Furthermore, when analyzing a signal we are not only interested in its oscillations, but where those oscillations take place.

The basic idea is to compute how much of a wavelet is in a signal for a particular scale and location: a signal is convolved with a set wavelets at a variety of scales. In other words, we pick a wavelet of a particular scale (like the blue wavelet in the animation). Then, we slide this wavelet across the entire signal i.e. vary its location, where at each time step we multiply the wavelet and signal. The product of this multiplication gives us a coefficient for that wavelet scale at that time step. We then increase the wavelet scale (e.g. the red and green wavelets) and repeat the process.

There are two types of Wavelet Transforms: Continuous (CWT) and Discrete (DWT). Unlike FT, the “continuous/discrete” here does not refer to the property of input data. Definitions of each type are given in the Figure 2. The key difference between these two types is CWT uses every possible wavelet over a range of scales and locations i.e. an infinite number of scales and locations. While DWT uses a finite set of wavelets i.e. defined at a particular set of scales and locations.

Mathematically a great number of analyzing functions (e.g. Mexican Hat, Morlet) could be created (Torrence and Compo, 1998). The choice of the analyzing function is neither unique nor arbitrary and mostly dependent on the likeness between the time-series and the analyzing function. Specific descriptions and recommendations of the properties of the analyzing function can be found in the literature.

Mother, Father and Daughter Wavelet

The wavelets are scaled and shifted copies (known as “daughter wavelets”) of a finite-length or fast-decaying oscillating waveform (known as the “mother wavelet”).

Wavelets can be defined by the wavelet function ψ(t) (i.e. the mother wavelet) and scaling function φ(t) (also called father wavelet) in the time domain. The father wavelet is also used for smoothing/denoising.

The Daughter Wavelet is created changing the time index input of the variable from t to (t-b)/a in the wavelet function.

Here is a simple example for creating a daughter wavelet based on the Morlet function with scale a=0.5 and position b=3s:

a = 0.5

b = 3.0

t = range(-4, 4, length=200) # Wavelet support for t in [-4, 4] with 200 sample points

s = @. exp( -((t-b)/a)^2/2 ) * cos(5*(t-b)/a)

When the daughter wavelet has only scaling but no shifting, it is equivalent to the father wavelet.

Statistical Test

Intuitively, the WT coefficients near the edges of the time-series is less trust-worthy than in the middle. This observation can be captured analytically by performing a statistical test. Torrence and Compo, 1998 have demonstrated that, each point of the WT spectrum is statistically distributed as a chi-square with two degrees of freedom. The confidence level is computed as the product of the background spectrum (the power at each scale) by the desired significance level from the chi-square ($\chi^2$) distribution. When the WT spectrum is higher than the associated confidence level it is said to be “statistically significant.” Following this statistical test, we can obtain what is usually known as the cone of influence. See the MATLAB documentation for a live example.

In Production With Machine Learning

A nice post Multiple Time Series Classification by Using Continuous Wavelet Transformation introduces the idea of using continuous wavelet transform as a tool for data cleaning before feeding into convolutional neural networks. This is really a sweet spot where we can combine available math tools together to solve problems.

Tools

MATLAB

MATLAB has a mature wavelet toolbox.

Python

Julia

The main package for wavelet in Julia is Wavelets.jl. Note that as of version 0.9.3, this package only supports discrete wavelet tranform. As an extension, ContinuousWavelets.jl implements the continuous wavelet transform, with some examples of scaleograms as well. I’m contacting the authors to see if it’s possible to extend the package even further.

-

The original inventors of WT used jargons like “dilation/contraction/translation” to describe the processes. I prefer to call them scale and shift. ↩